Software and the sonic subconscious of the digital OER

Section outline

-

-

Listen to the cover of a-ha's Take on Me by YouTube user Power DX7. Do the other 80's hit songs on the video sound familiar? There are plenty more videos like this on YouTube if you search for "dx7". Have you got strong opinions on 1980s pop-music, or "the 80s sound"? What would you say are the differences between typical 1980s sound compared to typical sound of the 1970s and the 1990s?

-

Install and poke around in Dexed, a free software FM (frequency modulation) synthesizer to explore more complex FM tones. It comes with many preset sounds, and you can modify them as you want. Start simple. Many interesting sound presets are available online by other people, including all the DX7 sounds. You can use the computer keyboard from A to L for white keys in 4th octave, and the keys above for the black keys like a piano. Each piano key corresponds to a musical note, and is actually specific frequency, you can google for the frequencies.

-

Simon Hutchinson talks about FM synthesis and computer games (6 minutes).

-

-

-

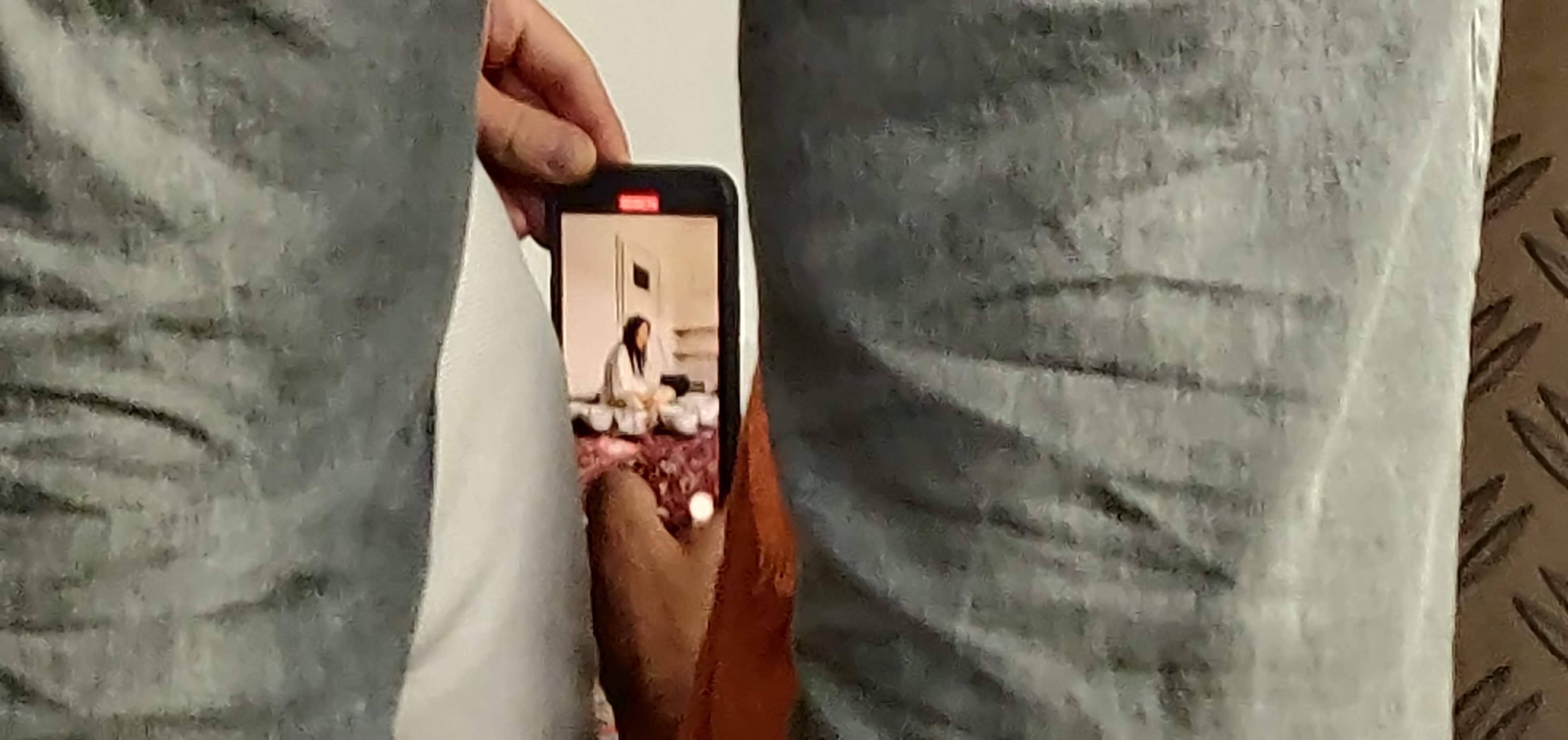

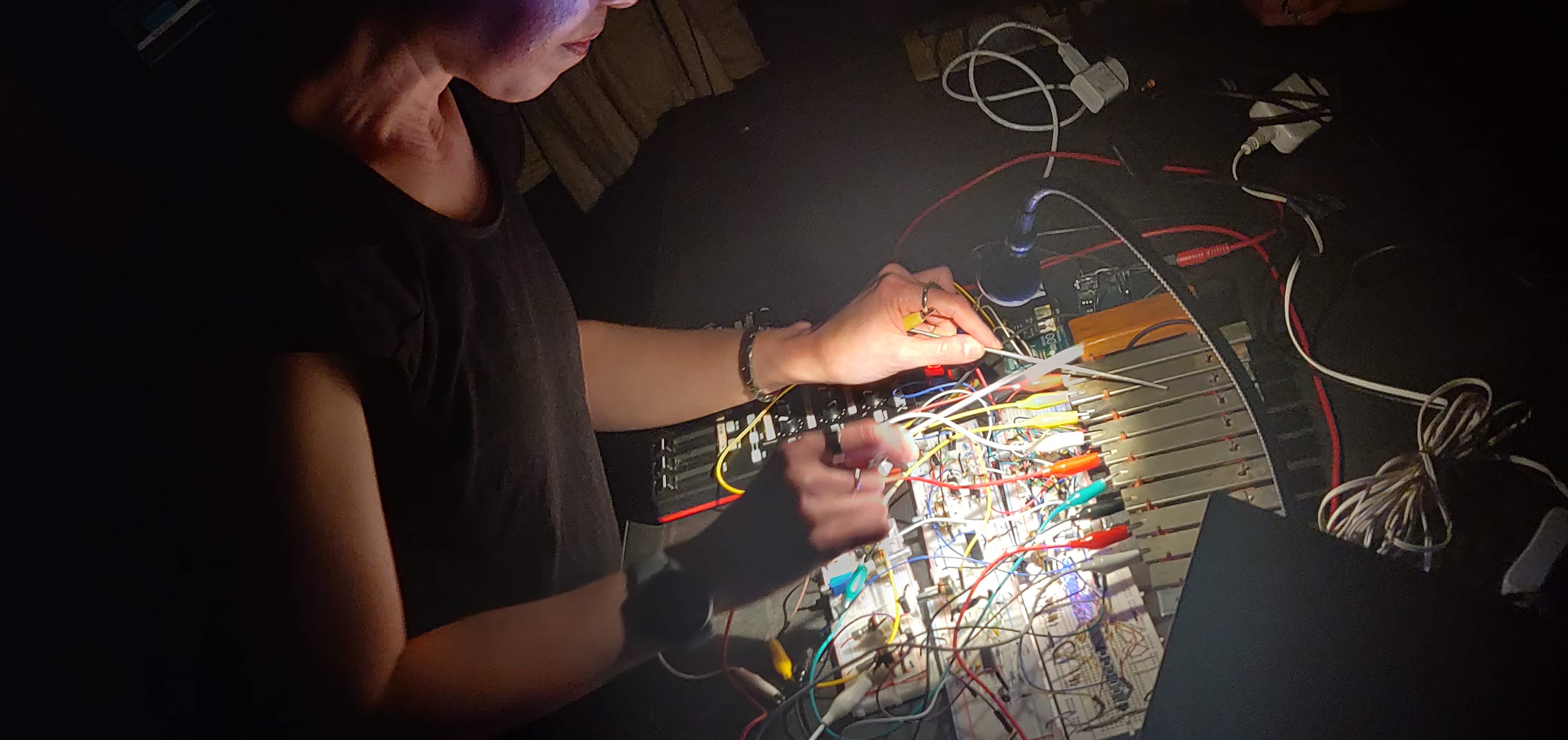

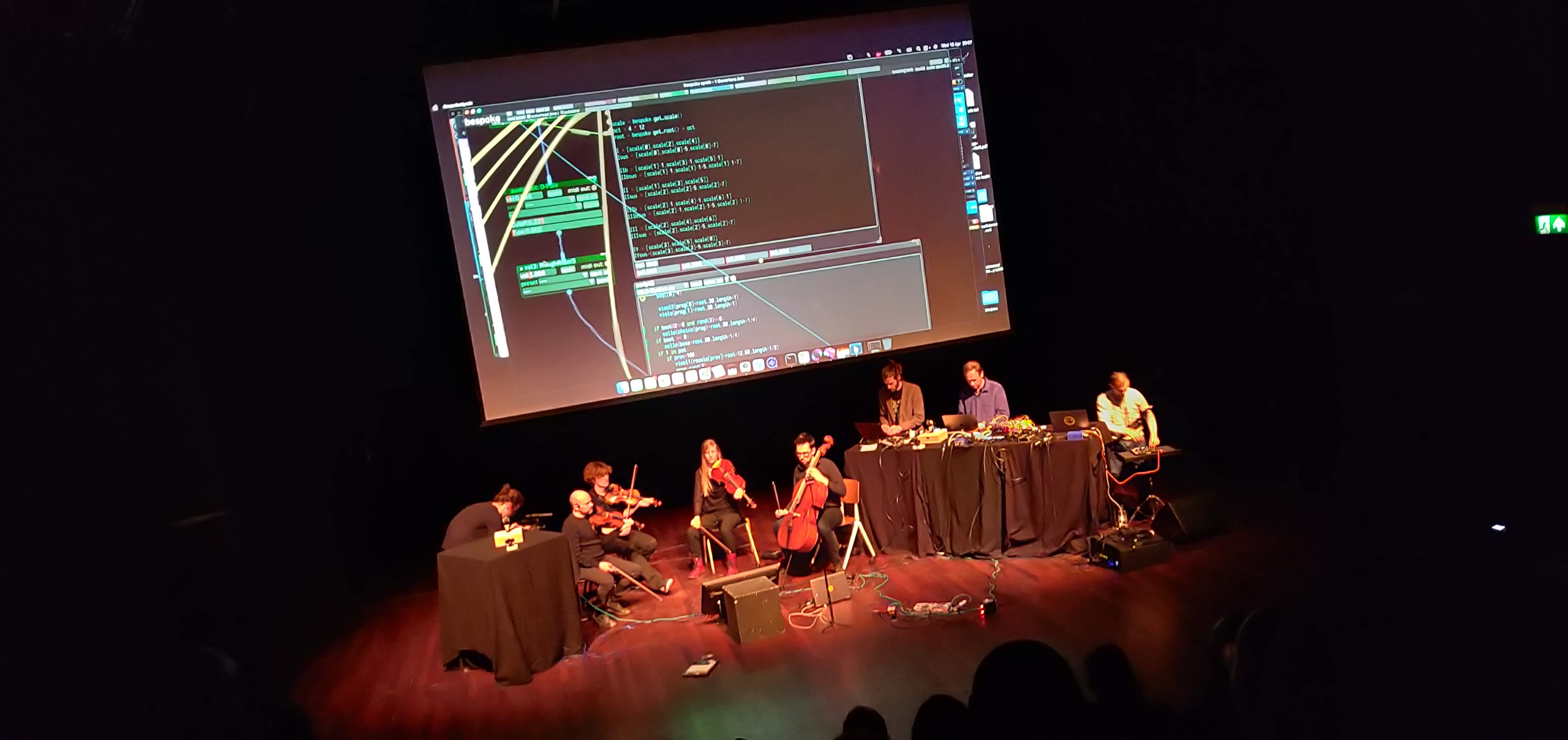

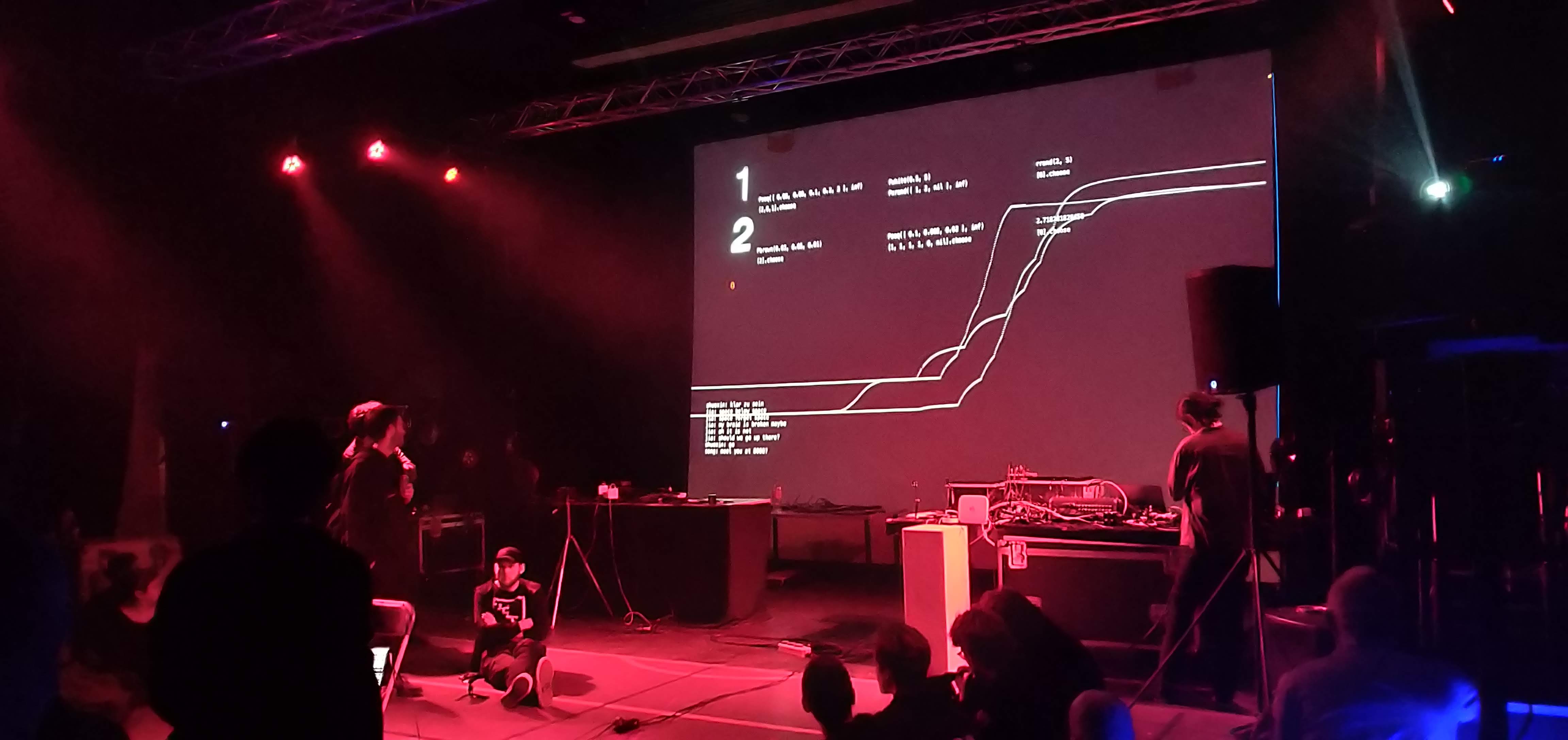

International Conference on Live Coding (ICLC) 2023 too place in Utrecht. "Live coding" aka "on-the-fly coding" is a musical and artistic practice to make music with computer programming. The community is very open, and concerts/algoraves are often accompanied by workshops. The community has a strong punk/D.I.Y. ethos. ICLC 2023 was complemented by a month of local satellite events around the world. The partymode is called "algorave".

Photos from ICLC by Mace Ojala.Here you can see the talks/presentations on YouTube at https://www.youtube.com/@incolico, and there is also an archive on YouTube.

Photos from ICLC by Mace Ojala.Here you can see the talks/presentations on YouTube at https://www.youtube.com/@incolico, and there is also an archive on YouTube. -

An exhibition documentary about the work of Ryoji Ikeda, by Zentrum für Medien und Kunst (ZKM) in Karlsruhe. Ikeda's work is an extreme, immersive example of "data sonification", turning data to sounds. You can see also e.g. his work at and in . Can you find some less extreme data sonifications online?

-

-

-

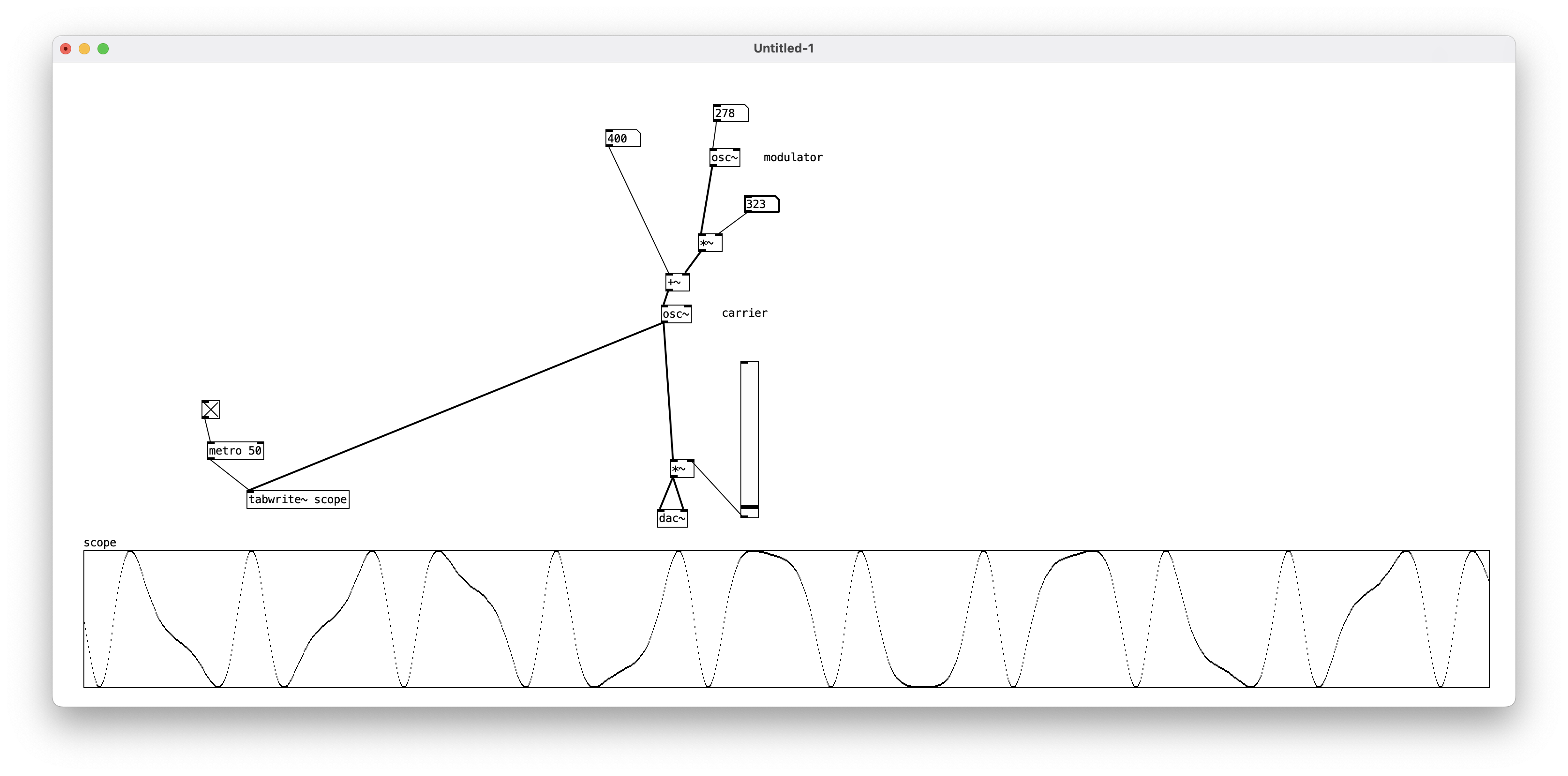

FM drone synth in Pd, corresponding to our first FM synthesizer we programmed with p5.js, called Synthesizer 3 above in section Let's build a synthesizer. Note the

[vslider]which serves as a volume knob has range from 0 to 1. We can observe some strange (read: fun) visual artefacts with default volume values 0-127, while the oscilloscope array has range 0-1.

FM drone program by Mace Ojala (GNU GPL v3), using Pure Data (BSD-3-Clause). Screenshot by Mace Ojala (CC BY-NC-SA) Can you read the p5.js and Pd versions side by side, and see how the objects correspond to one another.

FM drone programs by Mace Ojala (both GNU GPL v3), using p5.js (left; GNU LGPL) Pure Data (right; BSD-3-Clause). Screenshot by Mace Ojala (CC BY-NC-SA) If you make the values the same in both programming languages, do you hear minuscule or obvious differences in their sound? Surprisingly, with this Pd program you can make the carrier and modulator frequencies as well as the modulator depth negative, < 0. Does this mean time flows backwards? What if you make the volume negative, will the universe collapse in a reverse Big Bang? Can you do this in p5.js?

-

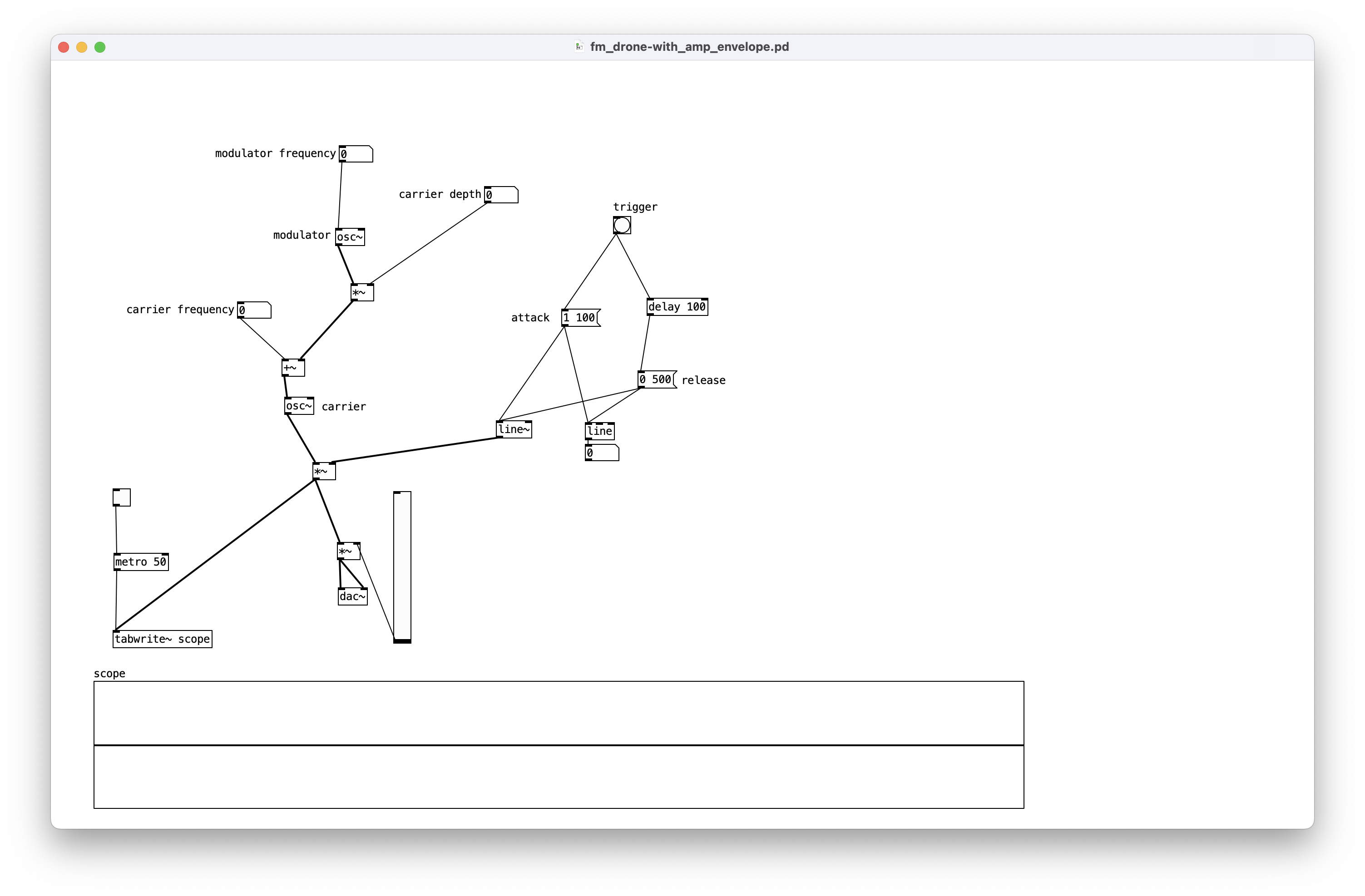

The second program (Pd programs are called "patches"), a version of the simple FM drone this time with an ampliture envelope. Click the

⧇object labeled trigger to produce sound. This corresponds to the Envelope FM synthesizer p5.js programmer earlier.

FM drone with amplitude envelope by Mace Ojala (GNU GPL v3), using Pure Data (BSD-3-Clause). Screenshot by Mace Ojala (CC BY-NC-SA) The envelope generator is the

[line~]object and it's parameters above it. The[1 100(,[delay 500]and[0 500(objects control the envelope attack, sustain (=note length) and release times. Try changing the values to produce a short sound, a long sound, a slowly appearing sound or a slowly disappearing sound. Can you connect the envelopes not only to amplitude but also to carrier and modulator frequencies? This is next level FM synthesisDX7 already had this feature, but you could expand the delay and message objects to produce crazy envelopes with more than three segments. How about six segments? Nine? What about 99?

The Prophet-5 on that track is a very nice synthesizer, but since it is analog rather than digital, it's out of the scope of this seminar.

-

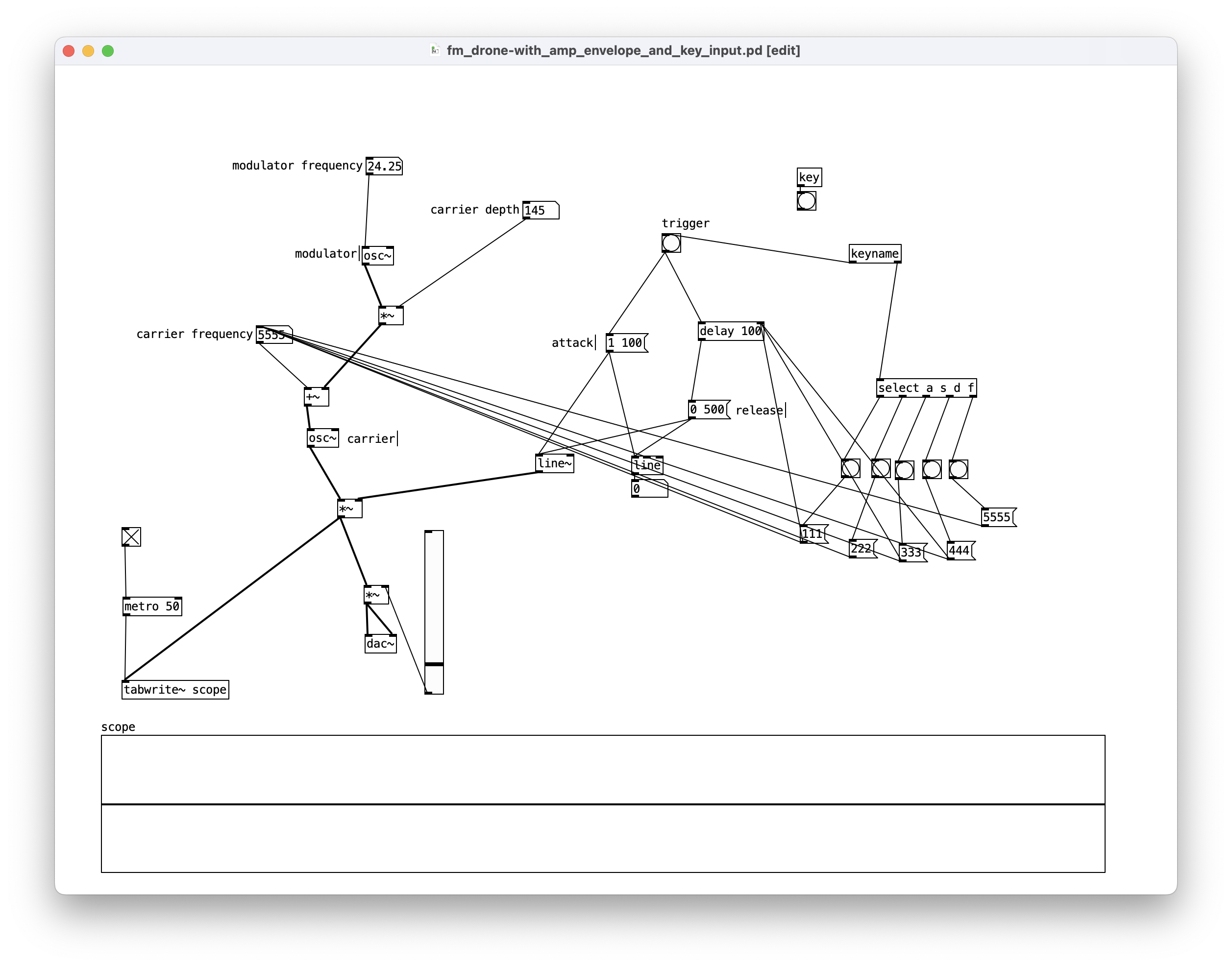

This Pd program ("patch"), extending the two above. This one responds to keypresses and play notes. The functionality is implemented by the

[keyname]object on the right, which is routed to different messages to change the carrier frequency.

FM drone with amplitude envelope and key input by Mace Ojala (GNU GPL v3), using Pure Data (BSD-3-Clause). Screenshot by Mace Ojala (CC BY-NC-SA) You could explore parametrizing the keyboard further, perhaps some keys would produce shorter, longer or louder sounds, or change the modulation parameters? We use the same word keyboard for the ⌨️ and 🎹. Could you invent an entirely new keyboard? Or could you tune the above to a familiar (or unfamiliar) musical scale, knowing that musical notes are names for certain frequencies.

-

-

This bleep was recorded on the 1st floor if building GB on RUB campus when Mace updated his transponder to get access to the seminar room on the 8th floor. It is therefore a sound of power, of access control, of legitimate rights, and of computer software.

-

In Proceedings of International Computer Music Conference, 2014. The abstract:

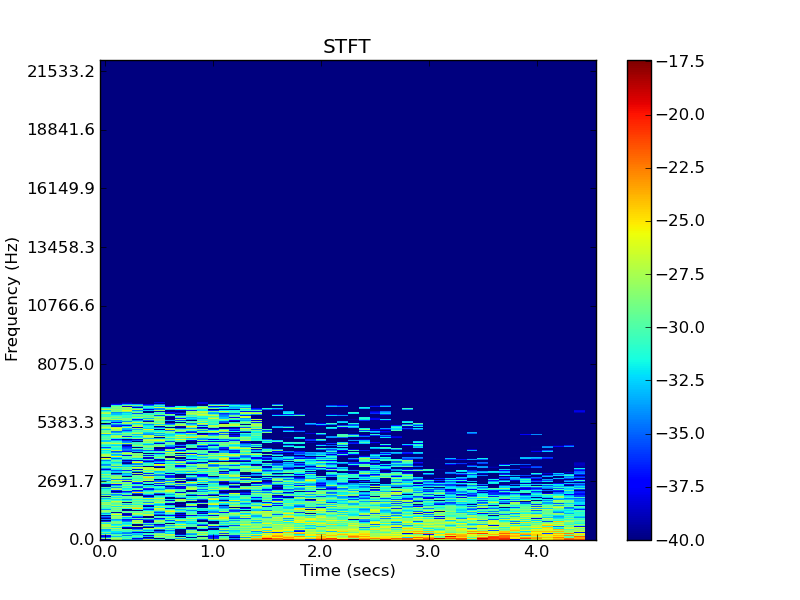

The MPEG-1 or MPEG-2 Layer III standard, more commonly referred to as MP3, has become a nearly ubiquitous digital audio file format. First published in 1993 [1], this codec implements a lossy compression algorithm based on a perceptual model of human hearing. Listening tests, primarily designed by and for western-european men, and using the music they liked, were used to refine the encoder. These tests determined which sounds were perceptually important and which could be erased or altered, ostensibly without being noticed. What are these lost sounds? Are they sounds which human ears can not hear in their original contexts due to our perceptual limitations, or are they simply encoding detritus? It is commonly accepted that MP3's create audible artifacts such as pre-echo [2], but what does the music which this codec deletes sound like? In the work presented here, techniques are considered and developed to recover these lost sounds, the ghosts in the MP3, and reformulate these sounds as art.

-

Ryan's project webpage theghostinthemp3.com with audio and image examples, and explanation of his process. Ryan also has them on Soundcloud if you want to focus on listening.

Image Example 2. White, Pink, and Brown Noise - Lowest Possible Bit Rate MP3 (8kbps) by Ryan Maguire, from The Ghost in the MP3 project website -

"SPEAR is an application for audio analysis, editing and synthesis. The analysis procedure (which is based on the traditional McAulay-Quatieri technique) attempts to represent a sound with many individual sinusoidal tracks (partials), each corresponding to a single sinusoidal wave with time varying frequency and amplitude."

Very strange -

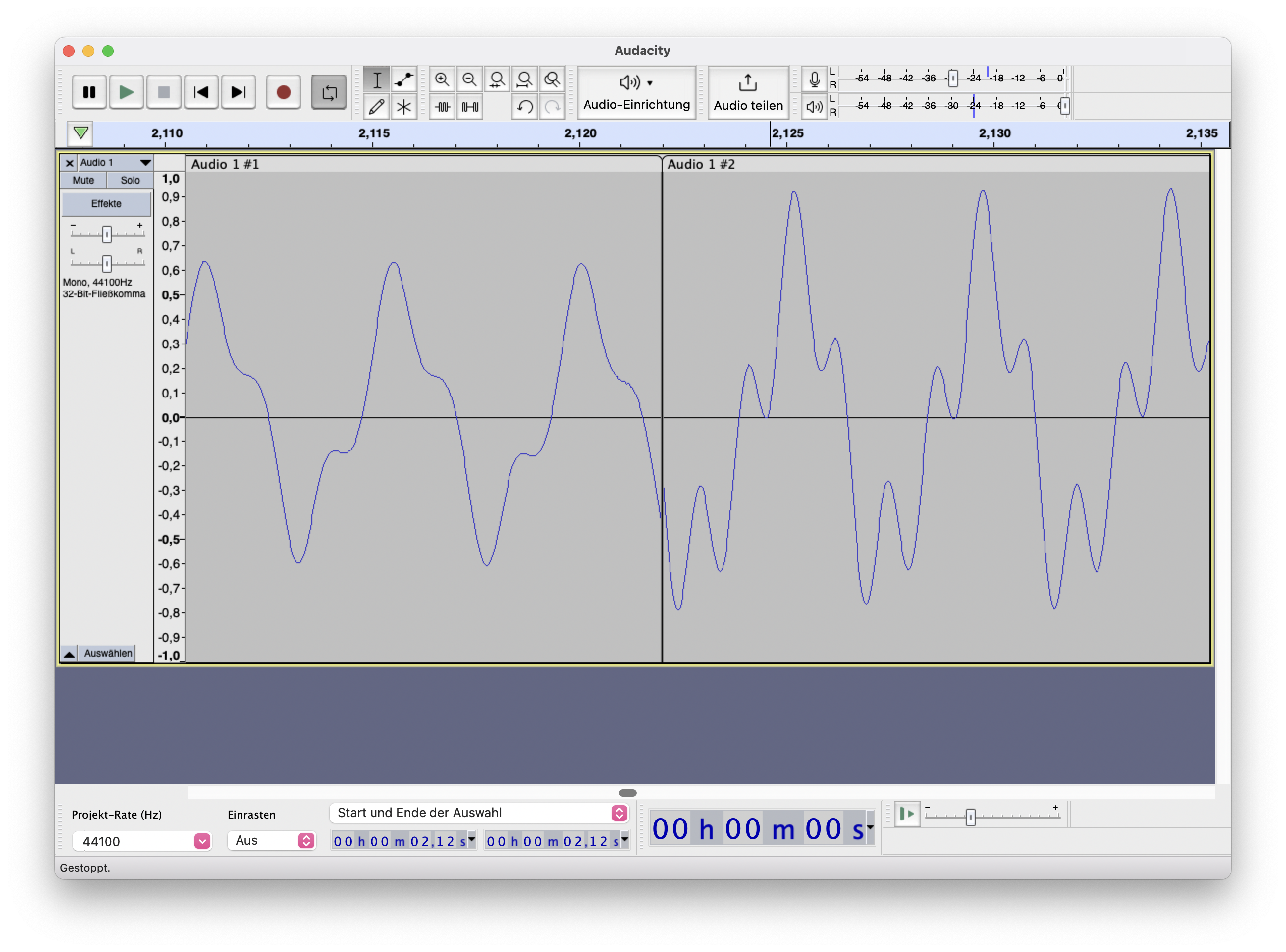

There was an observant question during the seminar about why the MP3 file is longer than the original WAV file. The reasons gets at the nittygritty of the MP3 file format, and it's encoder and decoder delays. See questions 1 and 2 in this FAQ of LAME, the MP3 encoder implementation Audacity uses.

-

One of the students has explored hauntology, breakbeats, computer fans and vaporwave in their music production. It's about hauntology, breakbeats, Computer fans, and vaporave somehow."

Ole also shared his Eratekk breakcore project album IFLF v1.1. What on earth is "breakcore", you might ask? Maybe listening leaves no need for clarification.

-

-

Here is a little digital instrument for you which combines concepts we have learned early in the course about synthesis with our recordings. What the program does, is transfer the amplitude ie. loudness.of a field recordings to the pitch of a synthesizer. Can you still recognize the original sound? Can make a copy of the program and use your own recordings to drive the sound? Could you imagine some other computer program which takes data from one source and uses it to generate something new in some other context?

-

Here is another digital instrument for you which manipulates a recording at a sample level, typically 44100 per second, and distorts it in unusually ways. Does this kind of distortion remind you of sounds you have heard earlier somewhere? Try making a copy, uploading a few seconds of your own recording experiments, and change the line 4 to point to your file. Use the three sliders to make new sounds.

Watch out, this can get really loud and noisy!

-

Mace encountered this sound when riding the bike in Dortmund home from one of the Blaues Rauschen concerts. Can you recognize it? Does it cause some affect in you, and what could the sound mean? What do it's waveform and spectrum look like? How would you describe the sonic qualities of the sound? Tip: it's a field recording from the street.

-

-

WDR Hörspielspeicher re-published the following audio-drama

On the Tracks - Auf der Suche nach dem Sound des Lebens

Here's the blurb from WDR.

Jeder Mensch ist ein Kosmos und trägt ihn folglich mit sich herum. Wohin? Das Hörspiel folgt unbekannten Menschen auf der Straße. Aus den Protokollen dieser Verfolgungen und der Musik von Console wird der Soundtrack von siebenmal Leben.

WDR Hörspielspeicher republication of Andreas Ammer's 50 minute audio drama On the Tracks - Auf der Suche nach dem Sound des Lebens, originally published by WDR in 2002.

Radio dramas are a quite a marginal and interesting format.If a public broadcaster like WDR (also Finnish YLE and Danish DR have some amazing productions both ongoing and backlog) wouldn't produce them, nobody would! On the other hand the second wave of podcasting is going well, and audio books are quite popular too. How would you characterize how audio dramas, podcasts and audio books differ from one another? How is an audio paper (Krogh Groth and Samson 2016) different from audio drama? How are they similar? What is good for what purpose? What stuff we have learned on this seminar would be useful for making audio dramas? Do you know some so-called "audio games"?

If you listen to the On the Tracks - Auf der Suche nach dem Sound des Lebens, how are the creators composing everyday sounds, music, tone, body-noises to create a mood, an atmosphere, a story and a sense of place and time? Is it convincing? What would you do otherwise? What machines, computers and software can you imagine in the drama?

-