Sound capture

Section outline

-

-

This bleep was recorded on the 1st floor if building GB on RUB campus when Mace updated his transponder to get access to the seminar room on the 8th floor. It is therefore a sound of power, of access control, of legitimate rights, and of computer software.

-

In Proceedings of International Computer Music Conference, 2014. The abstract:

The MPEG-1 or MPEG-2 Layer III standard, more commonly referred to as MP3, has become a nearly ubiquitous digital audio file format. First published in 1993 [1], this codec implements a lossy compression algorithm based on a perceptual model of human hearing. Listening tests, primarily designed by and for western-european men, and using the music they liked, were used to refine the encoder. These tests determined which sounds were perceptually important and which could be erased or altered, ostensibly without being noticed. What are these lost sounds? Are they sounds which human ears can not hear in their original contexts due to our perceptual limitations, or are they simply encoding detritus? It is commonly accepted that MP3's create audible artifacts such as pre-echo [2], but what does the music which this codec deletes sound like? In the work presented here, techniques are considered and developed to recover these lost sounds, the ghosts in the MP3, and reformulate these sounds as art.

-

Ryan's project webpage theghostinthemp3.com with audio and image examples, and explanation of his process. Ryan also has them on Soundcloud if you want to focus on listening.

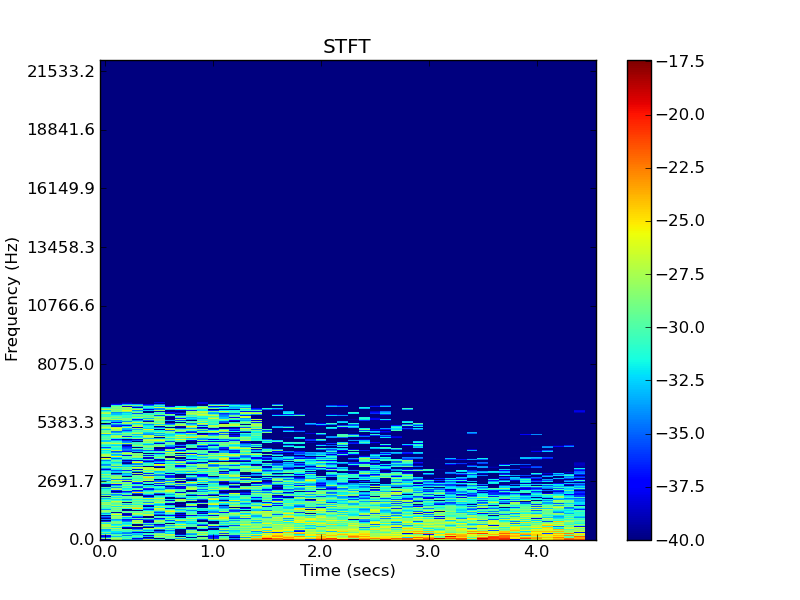

Image Example 2. White, Pink, and Brown Noise - Lowest Possible Bit Rate MP3 (8kbps) by Ryan Maguire, from The Ghost in the MP3 project website -

"SPEAR is an application for audio analysis, editing and synthesis. The analysis procedure (which is based on the traditional McAulay-Quatieri technique) attempts to represent a sound with many individual sinusoidal tracks (partials), each corresponding to a single sinusoidal wave with time varying frequency and amplitude."

Very strange -

There was an observant question during the seminar about why the MP3 file is longer than the original WAV file. The reasons gets at the nittygritty of the MP3 file format, and it's encoder and decoder delays. See questions 1 and 2 in this FAQ of LAME, the MP3 encoder implementation Audacity uses.

-

One of the students has explored hauntology, breakbeats, computer fans and vaporwave in their music production. It's about hauntology, breakbeats, Computer fans, and vaporave somehow."

Ole also shared his Eratekk breakcore project album IFLF v1.1. What on earth is "breakcore", you might ask? Maybe listening leaves no need for clarification.